This was the third distillery tour I enjoyed on our Kentucky Thoroughbred and Bourbon Land Cruise in May 2018. The Jim Beam Behind the Beam tour costs a whopping $199.00 and lasts four hours. Because of those two factors, my wife declined to join me for this tour. The tour was a fun and educational experience and, in my opinion, well worth the time and monetary investment. It was a delight to spend time with our guide, Jennifer, the distillery’s Trade & Hospitality Manager. She ensured that everyone’s questions, and I asked many, were fully and clearly answered.

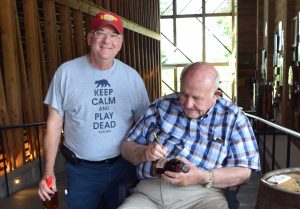

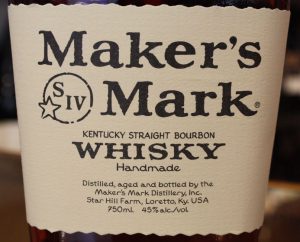

The highlight of the tour however, was the 90 minutes or so that our group of 24 spent with Master Distiller Fred Noe and his son Freddie. Both men were plain spoken, open and honest in their answers and explanations, and fun to be around. Fred Noe was especially entertaining, but did tend to use some salty language. Not an issue for an old Soldier like myself, but I can imagine some folks might be a bit put off. I highly recommend this tour for the serious bourbon enthusiast.

Jim Beam Ingredients

Jim Beam uses the famous Kentucky limestone filtered water, drawn from a nearby well, at each of its two distillery locations, for all its whiskeys. The well water is used as is for fermentation, but is demineralized for gauging or cutting the proof for barreling or bottling. Jim Beam sources its grains from multiple locations. It obtains corn from Kentucky and Indiana, rye from New England, and malted barley from North Dakota. All grains are milled on site on an as needed basis. Jim Beam uses a yeast strain, which they propagate themselves, that dates back to the 1930s. Jim Beam obtains its barrels from the Independent Stave Company. Each barrel receives a level 4 char, which requires about a 55 second burn. The barrels are not toasted before charring.

Jim Beam uses these ingredients to make a phenomenal number of products from the basic Jim Beam White Label to the highly regarded special “Booker” bottlings, such as the recently released Booker’s Bourbon Batch 2018-03 “Kentucky Chew”. This wide range of products helps explain the company’s dominance within the bourbon industry. There’s something for every taste and pocketbook. Between its two Kentucky distilleries, Jim Beam produces about half of all Kentucky Bourbon. Since about 90% of all bourbon produced in any given year comes from Kentucky, this means that Jim Beam is producing about 45% of the world’s bourbon. That statistic does come with an asterisk however. Jim Beam gets to claim its bourbon dominance only because the good folks at Jack Daniel’s choose not to call their fine Tennessee Whiskey a bourbon. If they did, they would be the world’s leading bourbon producer.

The Whiskey Making Process at the Plant #1

The milled grains and water drawn from the well are combined in the mash cooker. The cooked mash is then pumped into one of the plant’s 22 fermenters where the mash spends about 72 hours (3 days) to allow the yeast time to work its magic converting sugars into alcohol. Jim Beam, like almost every major bourbon producer, uses the sour mash technique, so some of the back set from an earlier distilling run is added to the fermenter along with the fresh mash. Once fermentation is complete, the mash, now called distiller’s beer, is pumped into the distillery’s column still.

The column still at the main plant in Clermont has 23 plates and stands about five stories tall. The distillate from the column still, known as low wines, comes out at 125 proof for most of the product line. Low wines for the Booker family of products comes out at 115 proof, which means more flavor and aroma compounds, good and not so good, are still in the distillate. The low wines move from the column still to a doubler that increases the distillate to 135 proof. Once again, the Booker line is handled differently and comes off at 125 proof. Plant #1 usually produces about 800 barrels per day, while the Booker Noe Plant produces about 1,100 barrels a day.

The new make is pumped into barrels and stored in one of Jim Beam’s many rickhouses. The company has more than 100 rickhouses scattered over the surrounding countryside. As of May 2018, Jim Beam has a little more than 2.2 million barrels of whiskey aging in its rickhouses. Once the aging process is complete, the barrels are returned to the distillery to be dumped. During our visit, they were dumping 3 year old Old Overholt Rye Whiskey. The whiskey is moved from the dump station to the bottling line, and then shipped out to wholesale outlets around the world.

Our tour took us to the Knob Creek Single Barrel dump station and bottling line. One person in our group had the honor of dumping a barrel, then we all moved to the bottling line. Once there we all had the opportunity to clean an empty bottle using Knob Creek left over from a prior bottling run. Also, for an additional fee, we had the opportunity to get our own personalized bottle of Knob Creek Single Barrel. I, of course, could not resist the siren call, and bought a bottle. Later, in the gift shop, I was able to get my bottle custom laser engraved, for yet another additional fee.

Tasting the Whiskey

Next stop on our tour was to Jim Beam’s oldest rickhouse, where we linked up with Fred and Freddie Noe. As I noted above, both men were a joy to be around and openly shared information with our group. As an example, one person asked how Devil’s Cut was made. I expected a marketer’s answer suitable for a TV ad. Instead, Fred Noe told us they simply add some water to the barrels after they have been dumped, and allow the water to sweat out some of the whiskey trapped in the wood. The extracted whiskey is then blended with other Jim Beam bourbon to make the final product. Once inside the rickhouse we sampled some Jim Beam straight from the barrel, using a commemorative glass that was ours to keep. Our 12 year old sample was dark, 118 proof strong, and full of flavor. Some really good stuff.

We moved from the rickhouse to the T. Jeremiah Beam Home where we ate lunch and sampled more whiskey with Fred and Freddie Noe. Here is what we sampled:

- Basil Hayden Dark Rye – A blend of Kentucky straight rye, Canadian rye from Beam’s Alberta Distillery, and California port-style wine. Bottled at 80 proof this was tasty and very easy to drink.

- Jim Beam Distiller’s Masterpiece – 10 year old Jim Beam finished in Pedro Ximénez sherry casks, bottled at 100 proof. I liked this one, but not enough to pay its high price to add to my bar.

- Knob Creek Cask Strength Straight Rye – This has no age statement, but Fred Noe said it was aged for 8 years in Warehouse A. Bottled at 119 proof, it is a challenge to sip neat. It is better on the third sip than the first. It is full of flavor and would make a wicked good Old Fashioned cocktail.

- Little Book “The Easy” Blended Straight Whiskey – the first whiskey created by Freddie Noe, it is a blend of 4 year old Jim Beam, 13 year old corn whiskey, 6 year old rye whiskey, and 6 year old malt whiskey. Freddie told us his goal was to recreate Jim Beam’s mash bill using finished whiskeys. At 120.48 proof, this really needs some ice or even some water to enjoy.

Of all the distilleries, large and small, I have visited over the years, this tour was head and shoulders the best. The tour was very informative, but the time we spent with Fred and Freddie Noe was what made the tour worth its $199 price tag. I enjoyed the experience so much that I intend to do it again sometime in the not too distant future. Assuming of course, I can convince my wife to let me spend the money.